DAVID DUNCAN

With a Foreword by JOHN SAVILLE

The Socialist History Society

Occasional Papers Series: No 8

original printed version ISBN 0 9523810 6 0

Foreword by JOHN SAVILLE

I

The history of discontent, unrest, strikes and mutinies in the British armed forces in World War Two has never been adequately documented. Mutiny is, of course, the accepted legal term for almost every refusal to obey orders. The story in this text offers a contemporary detail which is unusual. There is very little in the Public Record Office of events at Drigh Road RAF station, some few miles from the city of Karachi, which form the subject of the story which follows, and it is doubtful if much has been withheld. One can never be certain, since the British establishment has a remarkable and disreputable record of secrecy about events in which the government or any of its institutions have been involved, but it is unlikely. There have been more dramatic events of which the mutiny at Salerno is an obvious example, but the documentation of the “incidents” at Drigh Road offer an unusual and important insight into the psychological attitudes, and the daily practices they allowed, of the top levels of the military command.

The history of discontent, unrest, strikes and mutinies in the British armed forces in World War Two has never been adequately documented. Mutiny is, of course, the accepted legal term for almost every refusal to obey orders. The story in this text offers a contemporary detail which is unusual. There is very little in the Public Record Office of events at Drigh Road RAF station, some few miles from the city of Karachi, which form the subject of the story which follows, and it is doubtful if much has been withheld. One can never be certain, since the British establishment has a remarkable and disreputable record of secrecy about events in which the government or any of its institutions have been involved, but it is unlikely. There have been more dramatic events of which the mutiny at Salerno is an obvious example, but the documentation of the “incidents” at Drigh Road offer an unusual and important insight into the psychological attitudes, and the daily practices they allowed, of the top levels of the military command.

The major issue which brought about the demonstrations at Drigh Road was demobilisation, and this had inevitably been of growing importance from the day the war ended. There were, however, special reasons for anxiety among the RAF, for almost from the beginning of peace there were rumours that the pace of demobilisation for the RAF was likely to be slower than for the other services. John Strachey was the Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for Air in the new Labour government and on 17 October, 1945 – just over two months since the war ended – he wrote a long minute to his senior colleagues in the Ministry. There had been a debate in the House of Commons the week before on the slower rate of demobilisation for the RAF which had been planned from January to June, 1946, and Strachey acknowledged the widespread concern. His minute continued:

“My line in defence has been the obvious one that: first, a relatively large R.A.F. and small army is by far the most economical way of meeting our world commitments; and second, that we face a huge transportation and trooping task, largely for the sake of the other two forces …. But the hard fact remains that we are proposing to release only 140,000 men in the first six months of next year: that means only three groups in six months: and that is a far slower rate of release, either than we ourselves are achieving this year, or than the other two services will be achieving next year.” This paragraph was underlined for emphasis in the original, and his next paragraph opened with the words: “Frankly, I don’t think we can hold such a position” (PRO AIR 8/790/2157)

I am writing this foreword because although I was not in the RAF I was present at all the political discussions within the communist group in Karachi, and I was active in the defence and release campaign in the UK. I had been called up in the spring of 1940, into the Artillery, and although I was a university graduate I refused an officers’ training course on three occasions. In 1943 I became an Instructor in Gunnery, an elite group within the Artillery, and when not in the field there was always a good deal of independence for its members. I already knew a good many Karachi people as well as the local communists, and it was in the “bungalow” (a very large house) of a well-to-do Muslim friend of mine that the communist group sometimes met.

At our meeting which followed the Saturday morning refusal of duties at Drigh Road we had first to decide whether the communist group should become involved, and becoming “involved” meant providing the leadership. The Drigh Road group were agreed that that there was no choice since otherwise there would have been something like mindless chaos. Two questions then followed. There had been some calls from the men for a more prolonged strike, but like Arthur Attwood I myself was strongly opposed. To maintain a strike in an industrial situation at home is not always easy, but to expect the kind of solidarity required from a large mass of mostly apolitical airmen subject to military pressures all around them was unrealistic. I should add here that I was probably more conscious of the bastardry the top levels of the Services were capable of than some of my comrades. I knew the outlines of the stories of Salerno and the Cairo Parliament and I certainly knew more of military regulations. Arthur, with his industrial background, was fully aware of the problems involved, and we moved on to consider what demands could be worked out both to satisfy the wholly legitimate anxieties and complaints of the rank and file airmen, and to offer a genuine basis for discussion with the RAF authorities. What I have to add is that I had great confidence in Attwood, David Duncan and their comrades. Arthur throughout exhibited a steadfastness and common sense that evoked a remarkable response from the airmen of his station; and he had Duncan, Ernie Margetts and others in the group to talk matters over. Arthur had great abilities of leadership but this was a situation in which collective discussion and responsibility was of central importance.

As the story which follows makes plain, within less than a fortnight it really looked as though the demonstrations and the negotiations which followed had succeeded. At this point, either late in January or early February 1946, I myself left Karachi on the first stage of the journey to England, demobilisation and civilian life. It was over two months before I had any contact again with my friends from Drigh Road. Within three days of arriving in England, I received the telegram referred to in the text below: “Arthur arrested. Please help. Dunc”.

II

I was due to enter a new job when my demobilisation leave finished. This was in the economic research section of the Ministry of Works in Whitehall and my time during the day was therefore bound to be limited. On receipt of the telegram I went to King Street and saw Michael Carritt who a few years earlier had resigned from the Indian Civil Service. He had ended his career in Calcutta when Sir John Anderson was Governor, and his reminiscences are told in a riveting book, A Mole in the Crown, which he had to publish himself in 1985. Michael advised me to write to D N Pritt, the independent socialist MP for Hammersmith North, setting out all the details as far as I knew them in preparation for a meeting. This I did and then went to see Pritt.

He was a man of great personal charm, with a wonderful sense of humour and witty story-telling of high degree. He had been elected Labour MP for Hammersmith in 1935, expelled from the Labour Party in 1940 for supporting the Soviet invasion of Finland, and during the election year of 1945 had tried very hard to persuade the Labour Party to accept him back and to stand as the official Labour candidate. In these attempts he was widely supported round his constituency and within Westminster. But without success. When the results of the July general election came through, Pritt had 61 per cent of the total vote, an estimated 83 per cent of the Labour vote and the official Labour candidate lost his deposit: the only Labour candidate to achieve this in the whole country. To me at our first meeting Pritt was very helpful. We obviously needed the facts of the whole story, and these Duncan supplied. Duncan was our invaluable source of information from India since so many of the letters that Arthur was writing in these early days were being withheld. Pritt was always full of useful advice whenever I went to see him. He was never hurried although his workload was very heavy and he was always encouraging. He arranged for himself and others to ask questions in the Commons; he organised a deputation to see Strachey; and he wrote personally to Arthur and to Violet, Arthur’s wife. Pritt’s own account of the case, which he rightly thought important for establishing certain basic principles, will be found in part two of his autobiography, Brasshats and Bureaucrats, published in 1966. Without Pritt it is doubtful if we would have won.

Pritt was the greatest civil liberties lawyer of his generation, not only in Britain but also, and perhaps especially, for British colonies (for he could plead before the Privy Council). It was Pritt who did a superb job for Greek seamen during the Second World War, and it was Pritt who went out to Kenya in the fifties to defend Jomo Kenyatta. For those interested in the subtle paradoxes of twentieth century politics, Pritt, a man of compassion and a passionate opponent of injustice, when the facts were brought before him, was a hard-line supporter of the Soviet Union throughout his life. He died in 1972.

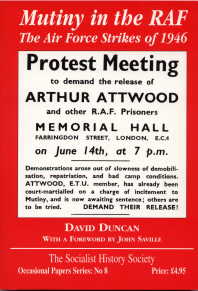

We were greatly helped, and much encouraged, by the extent of the trade union support we received, especially in the London area. Among those to whom King Street, the Party headquarters, directed me was Les Cannon who had been elected to the National Executive Committee of the Electrical Trades Union in 1945, at the time the youngest member. Cannon was later to become, in the closing years of the fifties, an implacable anti-communist in the group which took over the leadership and from whom Arthur Attwood himself was to be one of the subjects of their consistent hostility; but in the immediate post-war years and in the context of the campaign to win freedom for Arthur, Cannon was helpful. As were so many others, and the great Memorial Hall meeting which undoubtedly brought our campaign into the national news, included a major trade union contribution in its organisation and on its platform.

What must always be remembered is that there were dozens of mainly ex-RAF who contributed their share in writing letters to the press, to their MPs and who sent money from their own finances or from local collections. The victory in the Attwood case – which was to have its very positive effects on other cases – was the result of the efforts of many, whose contribution, large and small, made a national campaign. We needed above all the courage and steadfastness of Arthur Attwood himself, without which the work of Pritt and so many others would have been in vain. We needed also the constant flow of information from David Duncan from India. He himself was always vulnerable to the attentions of the security police and the modesty of his own account in the text which follows must not allow us to forget the important part which he played in this story. It was, as in all such cases, a two-way relationship: between the victim in prison and the large numbers outside. The campaign was an exhibition of the decency and the persistence of so many determined people for whom Attwood was the symbol of the constant struggle for democracy. And let us not forget, in all situations of the same kind, that the wives and families of the abused are under constant and continuous stress and travail. To Violet Attwood, whose quiet courage and determination throughout these very difficult days of 1946 was a notable addition to all our efforts, we offer the recognition of her indomitable spirit and the warmest of our respects.

JOHN SAVILLE, July 1998

Introduction

At seven-thirty on Thursday, 17 January 1946, eight or nine hundred men had gathered on the football field at Drigh Road, a large RAF maintenance unit near Karachi. It was dark. The sun had set more than an hour before, and no moon was visible. It was so dark that one could not recognise an immediate neighbour unless he struck a match to light a cigarette.

A few minutes later a voice called out from somewhere in the middle of the crowd, “You all know why we’re here…”

The men did indeed know. They were there because they had grievances. They were angry and they wanted action.

The decisions they took had consequences that reached far beyond Karachi.

1 Mutiny in Karachi

“In the middle of January, 1946, the British authorities, who had always feared the possibility of revolt in their Indian units, were shocked by a mutiny amongst the British” – Michael Edwardes1

I

Men in the forces are trained to obey. Parades, kit inspections, saluting, polishing boots and buttons may have other justifications, but all are used to accustom men to instant obedience to the orders of their superiors. How, then, could twelve hundred RAF personnel at Drigh Road in January, 1946, come to defy their commanding officer and take part in what was technically a mutiny?

In general, the morale of British forces during the Second World War seems to have been surprisingly good. That was certainly the case at all the RAF stations where I served during my time in India. There were plenty of grumbles, of course, and every reason for them – the heat, the flies, the disease, the abominable food, the lack of leisure facilities, the long hours of work, poor living conditions and, of course, the doubts about when wives, girlfriends and families would be seen again.

Men put up with all these things mainly because, almost without exception, they knew that this was a war that had to be won. They would have expressed this in different ways – fighting for their country, standing up for democracy, opposing aggression or, for me and many like me, fighting fascism. We all wanted the war to be over, but only after victory.

A few months after the end of the war the atmosphere had changed. Except for a few regular airmen, our paybooks showed that we had joined for “DPE” – the Duration of the Present Emergency. And to us the emergency was over. The war had been won. It was time to get back to Britain and then into civilian life.

Most men accepted that millions of servicemen could not be demobilised overnight, to flood the labour market and leave millions unemployed. But did many of us have to wait for years, which was what the current rate of demobilisation implied?

And if we could not be demobilised for a while, why could we not go home and serve our time in Britain? The official answer was that there were not enough ships, but none of us believed that. Some men pointed out that plenty of ships seemed to be available to take supplies to Indonesia to help the Dutch regain their hold on that country. Some drew attention to the great liners being made available to the “GI brides” – British women who had married American servicemen – to cross the Atlantic to the USA. Others asked whether it really mattered how many ships there were. There were hundreds of our aircraft at the disposal of the RAF, so why could we not be flown home? There seemed to be no official answers, and more and more men were convinced that we were being held in India as a matter of policy.

To make matters worse, there was a widespread belief that soldiers and sailors were being released more quickly than the men of the RAF. This was an impression gained from what was learned from friends in the other services, and we know now that that impression was totally justified. It was official policy to reduce the army and the navy more quickly. As John Strachey, Under Secretary for Air in the Labour government, explained in a confidential minute in October, 1945: “A relatively large R.A.F. and a small army is by far the most economical way of meeting our world commitments”.2 So most of us had to stay in India.

II

Peacetime had not improved our living conditions. Most of us slept in large barrack blocks, with a table and a couple of chairs in the middle, and a bed and locker for each of the thirty or so men. Each bed had a wooden frame, ropes instead of springs, and posts on which mosquito nets could be hung. For a couple of hundred men, even this accommodation would have been a significant improvement. They still lived in tents, many ragged with age.

My friend, LAC Arthur Attwood, was one of those to whom home was a tent. “Each of the bell-tents,” he noted, “perched on concrete plinths in rows, was the living quarters for up to six airmen, the sole furniture being a wooden locker and a bed criss-crossed with coarse twine … The legs were usually stuck into cigarette tins filled with water, the idea being to defeat the ants. There was also a greased ball round the tent pole, placed to prevent the little insects dropping from the roof canvas on to the charpoys (beds). Both methods were useless.

“The geckos were more welcome squatters. During the evening, by the light of the hurricane lamps, they suspended themselves upside down on the roof canvas, camouflaged as dirty white tent canvas, and stayed rigid, with long tongues suddenly snaking out to claim a fly or mosquito.”

Most of the men still worked long hours, some even longer than during the last few months of the war. And the food got even worse. The main course was usually a mush, ingredients unknown, and at one stage an important element of the main meal was the contents of a cardboard box – emergency rations obtained cheaply from the United States because they were no longer regarded by the Americans as good enough for their troops in the field.

“A few hundred yards from the tent,” Arthur wrote, “across the sand, was the cookhouse. It was in a hangar, with the swill bins nearby. The men would usually emerge from the mess, with knife, fork and plate, cross to the bins to deposit leftovers or, when they couldn’t stomach it, the whole messy plateful. There was always a line of big black, bedraggled birds on the hangar roof. Shitehawks! They would drop like a stone on the unwary or go straight for the swill bins.”

A little further on sat the fruit-wallah, selling oranges, bananas and roasted peanuts. Sweets and chocolate could not survive in the heat, so any after-dinner treat had to come from the fruit-wallah’s basket. Alongside stood a dish of coloured water – “pinky-pahni” to most of us. This was a solution of potassium permanganate, and we were expected to dip the fruit in the liquid to reduce the risk of infection.

There was no privacy, even in the toilets. The latrine most convenient for me was shielded by a fence, but inside there was only a huge, inverted wooden box. This had oval-shaped holes cut into the top along each side. Going in there each morning before work, one would see a line of men sitting along each side of the box, all with shorts or trousers round their ankles. Some would get in and out as quickly as possible, while others would loiter, having a chat with neighbours or perhaps reading a newspaper.

The climate, of course, added greatly to the discomfort. Long hours of work in the heat; the ubiquitous flies, mosquitoes and other insects; the diseases, of which dysentery and malaria were the most common. Few men who had been in India more than a few weeks had not had at least one spell in hospital.

One of the most common complaints, prickly heat, resulted from excessive perspiration. One could see a row of men in the mess, sitting at the table, and as they drank their tea after the meal, a damp patch on the back of each shirt would get larger and larger, as if the tea being taken by mouth was coming straight out through the back. This constant perspiration often caused prickly heat – the blocking of the sweat glands, with tiny red pimples forming, especially on the back and chest. These were so itchy that it was almost impossible not to scratch, yet scratching made things worse. Sometimes the pimples became yellow blisters, which could be very messy and sore.

For many men the biggest enemy was boredom. Most of the programmes at the camp cinema had little appeal, and the cinemas in the town of Karachi showed only Indian films. There were no billiard halls, no pubs, no professional football matches, no dance halls. So men were deprived, not only of family life, but also of the kind of organised entertainment that would have been available at home.

There was a small library in the education department, but the mostly old books had little appeal. Some men were sent newspapers from home and these were passed round among friends and were read eagerly. There was also a discussion group, but this was always a minority interest and in any case met only once a week. Occasional football matches took place between different sections of the camp, but there was little else in the way of sport.

So in the evenings men had something to eat in the canteen (there was no NAAFI) or they chain-smoked while playing cards in the billet. For anyone not interested in cards, life could be very dull indeed. For the most part they just dreamed of going home. Going home! That was all that men wanted, now that the war was over.

Getting home meant more than just escaping from India and the RAF. Men’s futures were at stake. Only a minority of the men had safeguarded jobs to return to. Most would have to go job-hunting, and they were impatient to get on with this. Others who had stayed at school until they were 18 and then joined the RAF, were now concerned about college and university places. Would these all be filled by the time they got home?

Many men were also anxious about their families. One or two had had “Dear John” letters, and this led a few others to feel uneasy. Most men had other concerns – the children’s schooling, everyone’s health, financial problems, even the impact of rationing (now in some ways worse than during the war). Men wanted to get home, to see girlfriends, wives and families again and to find reassurance. Early release – or at least a return to Britain – was of real importance.

III

The war was over, had been over for five months. To the men, that meant it was time to go home. To the top brass of the Air Force, that meant it was time for peacetime discipline. Early in January came the crucial blow. Station Orders announced that on Saturday, 19th January, the whole station would parade in best blue uniform, and the parade would be followed by a kit inspection.

It was difficult to know whether it was the best blue parade or the kit inspection which had most impact. A kit inspection! That meant setting out all our equipment on the bed, with the blankets folded in a particular way, and the remainder of the kit arranged in regulation pattern, so that an NCO or an officer could see at a glance whether any item was missing. And, of course, everything had to be spotlessly clean and, wherever possible, polished. But we had thrown away the absurd Victorian helmets we had been issued with; most of us had long since eaten our emergency rations and lost or thrown away lots of other useless gear. And who could remember how it all had to be laid out? Yet disciplinary proceedings could be expected to follow if anyone’s kit was found to be deficient.

As for parading in best blue! Our dress usually consisted of an open-necked khaki shirt and equally lightweight shorts or trousers, with socks and sandals. It was too warm, even in January, for anything more. Being in best blue was something different. It meant wearing a tie, putting on a heavy woollen uniform of tunic and trousers – clothing designed for warmth in the British winter. And in preparation, buttons and footwear would have to be polished and trousers pressed.

As men waited on the parade ground for the Commanding Officer’s inspection, a number of them would faint from waiting in the heat. Any man not turned out to the officer’s satisfaction would be “put on a charge”.

All this was infuriating in itself, but behind it lay something else. We could no longer pretend to be civilians waiting to go home. Suddenly we were involved in the bureaucracy and bullshit of the peacetime forces. The men could not accept that.

IV

The story began to circulate that a meeting of the men would be held on the football field on the Thursday evening at seven thirty, by which time it would be dark. No one seemed to know who had called the meeting, but it soon became clear that most of the men intended to be there.

I turned up on the football field in good time and found there were hundreds there already. My guess was that well over half of the men attended, perhaps eight or nine hundred, but it was impossible to tell. It was dark, so dark that it was difficult even to recognise the man at one’s shoulder. Men were engaged in the usual chat and banter, waiting and wondering whether anything was going to happen. And then it did. Someone in the centre of the crowd called out – I remember the exact words – “You all know why we’re here.” Everyone looked to where they thought the voice was coming from, and it continued, “Don’t look round. And don’t say anybody’s name”. The man then added something about Saturday morning.

For a few seconds there was absolute silence, and then a great hubbub began. It was clear that whoever had called the meeting had no procedure in mind, no plan to propose, and apparently no intention of playing any further part in the proceedings. Men were obviously very angry about both the parade and the kit inspection, but the meeting was becoming chaotic as several men shouted against one another, some protesting about grievances, others suggesting different remedies.

At this point Arthur Attwood made himself heard. He intervened because, of all the hundreds there, he was the only one who had both the nous to know what to do and the guts to do it. His voice boomed out above all the others. I cannot remember his exact words, but he said, in effect, “We won’t get anywhere like this, lads. We need a chairman to see that there’s one speaker at a time. Does anyone object if I do the job?” There were murmurs of approval and no opposition, so Arthur took charge of the meeting. He saw to it that only one man spoke at a time; he gave to the meeting the gist of anything said by a speaker in too quiet a voice; and he made sure that everyone was aware of the issue before a vote was taken.

Various suggestions were put forward, ranging from a full-scale strike, starting the next day, to a deputation to the CO, but consensus was reached in a surprisingly short time, and the whole meeting was over in not much more than half an hour.

Unanimously, we resolved that on the Saturday morning:

- we would not prepare any kit for inspection

-

we would go to the parade ground at the scheduled time, but wearing khaki drill, not best blue, and we would refuse to parade;

- anyone who had the opportunity to talk to the commanding officer would make it clear that we had strong grievances which we wanted to put to higher authority.

As I lay in bed on the Friday evening I wondered what would happen next morning. I was confident that all the men would keep to the agreement reached at the mass meeting; but our strike would be seen by the authorities as mutiny. Some weeks earlier there had been a strike of RAF personnel at Jodhpur, and we had heard that the CO had called in the Indian army. Would we also have to face the bayonets of British or Indian troops? Or would we be left on the parade ground in the hope that demoralisation would set in and the men would begin to disperse? Or could it all end in an amicable discussion? It was impossible to tell. Anyway, the decision was more likely to be made in Delhi at air headquarters than in Karachi.

In the event, all the men appeared on the fringes of the parade ground at the scheduled time, and all were in khaki. There was not a blue uniform in sight, and it must have been obvious to the station warrant officer and to the commissioned officers – though they were not immediately visible – that there would be no CO’s parade that day.

There was an air of tension now that had not been there at the Thursday meeting. This was the moment of truth. None of us – unless anyone had arrived recently from Jodhpur – had ever been in this kind of situation before. So we waited, not afraid – there were too many others in the same boat for that – but concerned. There was a lot at stake.

It was some time before the CO appeared. No doubt the telephone line to Delhi had been humming. The men were spread around the edge of the parade ground, but the CO approached the nearest group, and several of the men spoke to him vehemently but not threateningly. Some emphasised a particular grievance, while others demanded a meeting with higher authority and a promise of no victimisation.

More men had now congregated round the group with the CO. He seemed to be harassed, but in conciliatory mood. Go back to your duties now, he said, and he would see that a senior officer from air headquarters came to hear our grievances as soon as possible, and I thought his words also implied that there would be no punishments. In fact, most of us had no duties to go back to, since the morning was to have been devoted to the parade and kit inspection, but we dispersed quite happily. Our first demand had been met, and no further discussion was needed. The crunch would come when we met the man from air headquarters.

2 Political Campaigning

“For the first time since the Parliamentary Army of 1646, troops in the field, and in the rear, were openly talking about politics, what the war was about, and what they wanted to come out of it….” – Anon.1

I

There were nine or ten Communists on the Drigh Road camp, and we met as a group. Contrary to what some people might imagine, this was not a cell of saboteurs or spies, but a group of young socialists wanting to do all they could to help in the fight against fascism and to contribute to the building of a prosperous, socialist Britain.

We liked to think that we practised what we preached, and many of us found inspiration in the example of the International Brigade. When the Spanish civil war broke out in 1936 it was because Franco and his supporters refused to accept the will of the people and sought to overthrow the democratically elected Spanish government. While Hitler and Mussolini were quick to provide help for Franco, the British and French governments refused any assistance to the republican side.

It was in this situation that the call was made for an International Brigade, people from many different countries who would face the might of Franco’s professional army and his foreign allies, not for money but for a cause – the cause of anti-fascism. Encouraged by the Communist Party, about two thousand young Britons joined the brigade, a large proportion of them from the ranks of the party itself. So while the British government was involved in appeasing Hitler, young Communists were dying on the battlefields of Spain.

In 1942 and 1943, when the Communist Party was calling for the opening of a Second Front, they meant an allied invasion of Western Europe, so that the Germans, already facing the Red Army on a thousand mile long front in the east, would have to fight in the west as well. In the spirit of the International Brigade many Communists in the armed forces offered to take part in the invasion. As a trainee wireless mechanic in the RAF in London, I wrote to my commanding officer, volunteering for commando training in order to take my part in the Second Front. His reply was polite and not unfriendly, but he insisted that, in view of the time and money spent on my training, I could best contribute to the war effort by using my technical skills in the RAF.

In India, where most of us were not directly involved in the fighting, we felt that we could contribute to the war effort in three main ways – by being good at our jobs and working conscientiously, by setting a good example in responding to discipline, and in lifting and maintaining morale.

When I was in Agra, the Communist group there was also working to improve relations between British and American airforce personnel. We had contact with a number of American comrades, and they invited us to have lunch at their base one day and meet as many as possible of their colleagues. I like to think that we made a good impression and helped to eliminate some of the strange ideas that some had of British people.

The most abiding impression of the visit, however, was of the abundance of the food available. We could scarcely believe it. There were several different meats on offer, for example, and a man could help himself to whatever he wanted! And there was a similar choice of drinks – hot tea, iced tea, hot coffee, iced coffee, mineral waters. It was better than Lyons’ Corner House!

After that we decided that it would not help to improve British-American relations to return the compliment and invite the Americans to share the unappetising stuff served in our mess. So we invited half a dozen of them to a meeting on our station to give a short talk and answer questions. The meeting was well attended and the Americans met with a good response.

To strengthen morale we reminded colleagues of the nature of fascism and the need to win the war, and we combined this with a vision of what life would be like in post-war Britain if we had the right kind of government. In presenting our ideas at Drigh Road, we made good use of the station discussion group, for which the Education Section was responsible, and which met each Monday evening. There were three of us on the committee, and we were very influential, because we were the ones with ideas about what should be discussed and often about who could give the lecture or lead the discussion. I recall Arthur Attwood giving a talk on trade unions, and I introduced a discussion on the British press.

On one occasion, we invited the Senior Medical Officer to speak on the subject of “So You Don’t Want a Baby”. In the days when there was no formal sex education in school and suitable books were not readily available, this was a useful as well as a popular subject. We had such a successful evening that we followed it a few weeks later with, “So You Do Want a Baby” and had an equally large attendance.

Many of our discussions were on post-war Britain, and this fitted well with official policy, which was to encourage discussion – though preferably with an officer having tight control – of issues like housing, health policies, the 1944 Education Act and the Beveridge Report on social security. Once Germany had been defeated and the Labour ministers had withdrawn from Churchill’s coalition government, our thoughts turned to the coming general election.

II

When Britain’s voters went to the polls on 5 July, 1945, it was for the first general election since 1935. There had been by-elections, of course, but for more than five years there had been a party truce, so even in by-elections there was no Tory-Labour confrontation. Candidates from the sitting parties were either elected unopposed or faced competition from independents, minor parties or the new Commonwealth Party.

Since 1940 the country had been led by a national government headed by Winston Churchill, and his popularity was a major factor in leading media commentators to anticipate a Tory victory in the general election.

But general opinion in the country had been moving leftwards. As people coped with the problems of wartime, whether facing the blitz or standing together in queues, many developed a new sense of community and began to feel that there should be a common cause in peacetime as well as in war. Government intervention had brought full employment, fairer shares (through rationing) and improved health for many of the people. Should not a peacetime government do the same? These views were encouraged by a new respect for the Soviet Union, based on sympathy for the millions of Russian casualties and admiration for the success of the Red Army in our common fight against Nazi Germany.

People also remembered the pre-war days and the Tory record. In their political history, Post-War Britain, Sked and Cook note that, “Churchill had lost the election because the voters refused to forget. They refused to forget the years after the First World War when Lloyd George’s promises went unredeemed; they refused to forget the depression years, the unemployment and the General Strike; and they refused to forget the failure of Chamberlain’s appeasement policies which Churchill himself had taught them led to the Second World War. In short, the voters refused to forget the failure of the inter-war period when political life in Britain had been dominated almost exclusively by the Tory Party”2. So, when the people voted, they gave a massive majority to the Labour Party, whose manifesto proclaimed that it was “a Socialist Party, and proud of it”.3

The men in the services were affected in much the same ways, and there is considerable evidence that they were more left-wing than the civilian population. Servicemen were old enough to remember the thirties, young enough to receive new ideas. Their interest in the progress of the fighting on the many fronts encouraged an interest in current affairs. The rigid class distinctions between officers and other ranks, which none could fail to observe, fostered a radical outlook.

Moreover, discussion within the ranks, especially about Britain after the war, had been officially encouraged, as a means of maintaining morale. In 1941 the Army Bureau of Current Affairs (ABCA) was set up to provide material for discussion on social and political issues, and it produced a series of booklets. Some politicians have perhaps exaggerated the influence that ABCA had in promoting Labour views, but in many units it did have considerable impact. Just as important, it developed a discussion culture throughout the services, and in hundreds of units debates took place, formal and informal, official and unofficial, on issues of the day, and especially on the character of post-war Britain. It was this atmosphere which enabled servicemen to set up mock parliaments, of which the most famous was the one in Cairo.

ABCA booklets were made available to the RAF. At Drigh Road this material tended to lie unused in the Education Section library, except perhaps when someone was seeking information for a talk to the discussion group. However, from the spring of 1945, if I remember rightly, it became policy to hold a weekly discussion class in each section, and two of the Communist group – Ernie Margetts and I – were among those recruited as discussion leaders.

The discussion group, which catered for the whole station, continued to function successfully, and when the general election was announced, the committee proposed that we hold a mock election, and the CO agreed. This would not be just a single meeting with a vote taken after short speeches by the candidates. We had permission for a week’s campaigning before the vote.

In the Communist group we were aware that only a small minority of the men would have general election votes in constituencies with Communist candidates, whereas virtually all would have the opportunity to vote Labour. So we decided to concentrate on attacking the record of the Tories in both home and foreign affairs and showing how much ordinary people would benefit from Labour’s policies; we would deal only briefly with the differences between Labour and Communist. I was nominated as the Communist candidate, but spent the critical week in hospital with malaria, and my place was taken by Jack Roth.

The Communist group, much better organised than the ad hoc groupings set up to work for the other parties, ran much the best campaign and did particularly well at open-air meetings. The day before the vote, the Communist candidate announced his withdrawal – as we had privately agreed in advance that he should – and called on the electors to vote Labour. We were delighted when the Labour candidate achieved a massive majority, and we had no doubt that in the general election itself the great mass of our colleagues would vote Labour.

All the members of the group made a weekly contribution to the funds. We once sent a substantial sum to Labour Monthly, a Communist-edited journal in Britain, but the bulk of our money went to support the local comrades of the Communist Party of India, with whom we were in regular contact.

Three members of the group – Arthur Attwood, Ernie Margetts and myself – played a prominent part in the January events and the follow-up. Arthur was 31. He left school at fourteen, became an electrician, and spent 12 years in the building industry. He was an active member of the Electrical Trades Union and a member of one of its regional committees. He could soon grasp the gist of an argument, was a good debater and, in challenging what he saw as injustice, could make speeches with powerful impact. D N Pritt, the Independent Labour MP, later described him as “a level-headed trade unionist of strong character and common sense”. His leadership qualities had been demonstrated at the Thursday meeting.

Ernie Margetts was an armourer, though before the war he had been training for management. He was 26. I enjoyed his company, partly because he had such wide interests and such enthusiasm. After the war he did some teaching for the station’s education section. When I attended one of his classes on the cinema, I was so impressed that I used both his material and his approach for a class of my own. I was sure that he would make an outstanding teacher, and it was no surprise to learn some years later that he had, in fact, entered that profession.

I was 21. After leaving school at 15 I had worked for nearly three years as a junior reporter on the local evening paper before volunteering for the RAF. Having failed the eyesight test for aircrew, I was sent off for training as a wireless mechanic. After the war I attended a short course on teaching and in January was awaiting my promotion to sergeant and a full-time post in the education section. I was secretary of the group. There was seldom any correspondence and there were no minutes to write, but there were meetings to be called and agendas to be prepared, and the title of secretary also implied some degree of leadership.

The group had played no part in calling the Thursday meeting. In his book, The Days of the Good Soldiers, Richard Kisch maintains that the Communist group at Drigh Road had met on the Thursday afternoon in “a bungalow on the outskirts of Karachi” and that Arthur was nominated to speak.4 There was no such meeting at that point. It was fortunate for all concerned that Arthur took charge, but he was not nominated by the group. Nor did he “speak” in the sense of advocating a policy. Like all good chairmen, he was seeking consensus – and got it. On the Friday I spoke to each of the members individually, and we agreed that at the Saturday morning demonstration we would avoid standing together but would spread ourselves round among the men. This was to ensure that each part of the crowd would have at least one of us to speak, shout slogans or give any other lead that was needed. That was the only collective decision the Communist group took at that point.

Although the group held its own meetings at Drigh Road, we also attended a regular, weekly meeting in Karachi on Saturday evenings. A group of us would go into the town in the afternoon and have our only good meal of the week in a cafe before going on to the Communist meeting. To these meetings came comrades from two other RAF bases, Mauripur and Korangi Creek, and there were also two soldiers – Ian Taylor, a Scot from the Royal Corps of Signals, and John Saville, who was a sergeant-major in the Royal Artillery.

John, who was 27, was our guru. Before going into the army he had graduated with first class honours from the London School of Economics. He was confident and articulate, had an immense fund of general knowledge, had read much of the work of Marx, Engels and Lenin, seemed to know all the details of the history of the Communist Party and was acquainted with a number of the party leaders and officials. We all had great respect and admiration for John and on difficult issues tended to look to him for guidance. He would later switch to an academic career and become Professor of Economic and Social History at the University of Hull, surely the first sergeant major to become a university professor.

On the day of the Drigh Road demonstration there was the usual Communist meeting in Karachi, and of course we reported on the events on our station, which became the evening’s discussion. I remember John Saville saying to us, “Either you’ve got to have nothing to do with this, or you’ve got to get in there and take over the leadership”.

We felt that we should take the lead, and it was agreed that the way forward was for us to find the men who had called the Thursday meeting and invite them to join us in a committee to plan the next steps. The most urgent task would be to prepare a series of demands to put to air headquarters, and we had some preliminary discussion on what those might be. I remember arguing strongly for sending a petition to the Prime Minister. It was a good meeting, and I woke up on Sunday morning feeling confident that I knew exactly what needed to be done.

III

The men had many grievances, but the most important demand was for a faster rate of demobilisation, and that was something we could not get from Karachi or Delhi. Only the government could decide that, so we needed a political campaign aimed at the House of Commons and the Labour government.

A petition to the Prime Minister would need to be sanctioned by authority, but every serviceman had the right to communicate with his MP. That did not require anyone’s permission – though some men would need convincing – so we had decided, on the journey back to Drigh Road on Saturday night, to launch a campaign to get hundreds of letters sent to MPs. Many men were uncertain about what to write, and some did not even know what address to use. So we needed suitable letters, and I spent Sunday morning writing various versions. Several colleagues helped by copying my drafts or making their own variations.

Other members of the group, commissioned to locate the men who had called the Thursday meeting, soon found the two responsible. The motivator was a lad known to all his acquaintances as “Geordie”, though in fact he came from Middlesbrough on Teesside, not from Tyneside. The other lad I did not know. But the two agreed to meet us that afternoon. There were, I think, just six of us at this meeting of what was, in effect, the leadership committee – the two we had found, Arthur, Ernie and myself, and one other member of our group.

We had put the word round that there would be another mass meeting on the football field that evening, and the committee meeting needed to produce a programme to put to the men. But there was another matter to be dealt with first. Someone else had called a meeting on the Saturday evening, at which there had been talk of a full strike on the Monday, but the attendance had been poor, and we quickly dismissed the idea of an immediate strike. We had achieved our first goal, and further use of the strike weapon was something to be held in reserve, in case our demands were not met or there was any attempt at victimisation.

Taking into account our discussions in Karachi, I then put to the committee a minimum six-point programme to meet both the basic issue of demobilisation and the issues which had triggered our demonstration.

These points were:

- Air headquarters to put our complaints over repatriation and demobilisation direct to the Air Ministry;

- Permission to be given for the circulation of a petition addressed to the Prime Minister;

- An official announcement to be made, making it clear that men always had the right to correspond with their MPs;

- The parliamentary delegation then visiting India to be asked to send one or more of their members to Drigh Road to meet the men;

- No kit inspections;

- No Saturday parades.

The meeting quickly agreed to these points, making only one small amendment – that our committee be flown to meet the parliamentary delegates, if that was what the MPs preferred. But there was general agreement that we needed to add demands about living conditions. Food, of course, was the first priority, hours of work the second. Some sections of the station required their men to assemble at a particular point each morning and then march to the workplace. We decided that that was ridiculous and had to be stopped. So we added three points, to make a nine-point programme:

- An investigation into the quality of the food served in the mess;

- A reduction in the excessive hours worked by most of the men (I am sure that we were much more specific here, but I cannot recall the detail);

- Cancellation of daily parades to work.

Our Sunday evening meeting was very different from Thursday’s. We had a chairman, a main speaker, a motion to put to the men, even a platform for the speakers. Arthur again took the chair. He quickly dismissed the idea of a strike, argued that the urgent need was to agree on what to say to the officer who came from air headquarters, and then introduced me (though not by name!) to present the committee’s programme.

It was a strange experience. As I looked down from the platform I could just make out vaguely at the back some tops of heads against the sky, and near the front some blobs that were faces. I was convinced that there were even more at this meeting than at Thursday’s. It might have been a stressful experience, but I was so confident that our programme was right that I felt no nervousness, and I explained in some detail our nine points. The men listened in silence, but the volume of applause at the end was a sufficient indication of their approval. Arthur put it to them in a formal way. Were we agreed about the nine points? There was a great shout of “Yes”. His question, “Is there any dissent?” was met by absolute silence. We could go forward united.

IV

At lunchtime next day the Station Warrant Officer came into the airmen’s mess to announce that Air Commodore Freebody had arrived from Delhi and would meet a delegation of twenty men at two o’clock. He then began to organise the delegation. Arthur and I were not there, but Ernie Margetts was. He and others protested, arguing that the men were quite capable of managing their own election of delegates. Arthur arrived at that point, soon grasped the situation and led the men off for an election meeting. Predictably, Arthur, Ernie and I were among the first to be elected.

The delegates then met and made only one decision – that we should repeat the pattern of the previous night’s meeting, with Arthur in the chair and myself as spokesman. With our nine-point programme we were ready for the Air Commodore.

Air Commodores are very superior people. An aircraftman could go for years without seeing one, and they seldom noticed “erks” (rank and file airmen) except to return an occasional salute. But Air Commodore Freebody turned out to be just the man for this particular job. He was on a mission of conciliation, and he did not bat an eyelid as Arthur told him that he, Leading Aircraftman Attwood, would chair the meeting and that LAC Duncan would be the spokesman.

I spoke to our points, one by one. After each point, the officer asked questions or made comments, and other members of the delegation then joined in to give support. It was quite an amicable meeting, and the Air Commodore eventually agreed to eight of our nine points. He could not agree that there should be no CO’s parades, but even here he made an important concession in accepting that best blue would not be required.

Eight-and-a-half wins out of nine was more than most of us had dared to hope for, and we left in jubilant mood. Another meeting was needed to report back to the men, and this was held in the mess. What happened to me at that point I cannot recall, but I was not at this meeting. Arthur and Ernie did the reporting back.

After this the atmosphere in the camp was transformed. We had won. Meals improved; overtime was reduced; there was no kit inspection or best blue parade to worry about; easy chairs had appeared; the worst of the tents were replaced by new ones; and we had the satisfaction of knowing that we had struck a blow for earlier demobilisation. There was a sense of camaraderie and solidarity. Arthur and I were the heroes of the hour. Men we did not know greeted us in the most friendly fashion. Quite a number came to us to seek advice on a surprising range of problems, domestic as well as service.

We still had much to do in following up the delegation. We had the letters to MPs and the petition to see to as well as keeping an eye on the administration. In fact, air headquarters and the CO kept their side of the bargain. They did arrange for Harold Davies, the Labour MP, who was in India at the time, to come to the camp and speak to a meeting of the men. The men were very civil, and there was no abuse or unpleasantness, but he must have been impressed by their obvious determination to have a faster rate of demobilisation.

Nor did the CO make any attempt to interfere with our political campaign. He did call a meeting of the whole camp and told us how serious had been our action. He made it clear that any repetition would be dealt with severely, but he repeated his earlier undertaking that there would be no punishments on this occasion.

I began to wonder about that when Arthur and I were the only two non-commissioned personnel to be called to give evidence at a court of inquiry into the affair; but we were asked only to explain what grievances had driven the men to take such extreme action, and we faced no leading questions about our own activities.

Meanwhile, we were busy with the campaign aimed at Westminster. Some of the men were happy to write to their MPs at great length, but for others it was hard work. Many had to be convinced that a few spelling errors did not matter, others that they could copy one of our draft letters if they found it difficult to put the issues in their own words, and some that there would be no victimisation. But we had a great deal of success, and I have seen an estimate that five hundred men sent letters.

I would not have thought the number to be quite that large, but it must have been approaching four hundred. There is no way of knowing exactly. But even a figure of three hundred would have been an outstanding achievement – more than some national campaigns can manage.

The other big job was the petition to the Prime Minister. I had already drafted this. The problem had been to find a form of words that had real political importance and yet would be acceptable to all the men. When I re-read it in a book some time ago, I had difficulty in recognising it. I had thought it much crisper and shorter. At the time, however, I was very proud of it, and it certainly captured the imagination of many of the men.

The petition read,

“We, the undersigned airmen of Drigh Road, India, are gravely dissatisfied with the slow rate at which demobilisation and repatriation are proceeding. Although the war ended five months ago, there are still thousands of us without any indication as to when we shall see our families and friends again.

“Why is this? We have not been convinced by official reasons. Why cannot demobilisation and repatriation be speeded up?

“Is it because faster demobilisation would flood the labour market at home? We expect full employment from the Labour government we are proud to have helped elect.

“Is it because British policy in India and Indonesia requires large armed forces? If so, we demand a reversal of this policy.

“Is it because the government wishes to talk tough to other powers? We deplore such an attitude in the United Nations.

“Is it because of obstruction from any quarter? We expect the government to overcome such obstacles. You can be sure of our full support.

“We have done the job we joined up to do and now we want to get back home, both for personal reasons and because we think that it is by work at home that we can best help Britain.”

A number of men were very keen to help with the petition, but they wanted the job to be done in style. So instead of circulating scores of foolscap sheets for signature, someone produced a large roll so that the whole station could sign on the one paper. An airman with some skill in calligraphy copied the words of the petition so that it looked like a manuscript from some medieval monastery. And one of the workshops produced a box that would accommodate the roll and allow it be wound on for the next set of signatures.

This box was carried enthusiastically from barrack block to barrack block and from tent to tent, with everyone expected to sign. And they did. We had to go to some blocks a second and third time to catch those missing at first, and still there were individuals to be chased up. But eventually we reckoned that we had some twelve hundred signatures – everyone on the camp below the rank of sergeant, with one solitary exception, a corporal who refused to sign because of some obscure principle. We sent the Prime Minister advance notice by telegram and then posted the roll.

The petition was the lead story in the Daily Worker. “RAF Strikers Petition Mr Attlee” ran the banner headline across the top of the front page. The other papers ignored the petition at first, though a number mentioned it when the matter was raised in Parliament.

On 13 February Mr E Fletcher asked the Under Secretary of State for Air if he was aware of the dissatisfaction felt at the RAF station at Drigh Road and to what extent men were being held back from demobilisation in anticipation of trouble during the forthcoming elections in India. John Strachey dismissed the second point – “these men are certainly not being held back from demobilisation” – but agreed that “representations in the form of a petition to the Prime Minister” had been received and the “petition is now under consideration”.5

3 A Wave of Mutinies

“Only in 1946 did a series of mutinies have the effect of galvanising the British government. The first of these incidents, involving RAF servicemen enraged by delays in demobilisation and repatriation, was, in a sense, the most shocking. But units of the Indian Air Force were the next to mutiny, and much worse was to follow”. – Denis Judd1

I

The circumstances which led the men of Drigh Road to take action were matched elsewhere, and news travelled fast from one station to another – by teleprinter, telephone and radio. So the Drigh Road affair acted as a trigger to release mass activity at one RAF station after another.

From the Middle East to Singapore the rank and file of the service took action. In a speech to the House of Commons on 29 January, Prime Minister Attlee said that “incidents” had occurred at twelve RAF stations, but the Air Ministry later put the figure at 22 stations. The number of units, as distinct from stations, was much higher. According to a “Secret History” programme broadcast on Channel 4 in 1996, there were strikes at more than 60 units, with more than fifty thousand men involved. These “incidents”, some lasting only a few hours, others up to four days, all took place within eleven days of the initial protest at Drigh Road. It was the “biggest single act of mass defiance in the history of the British armed forces”.2

The strikes had two things in common. The main demand of those taking part – whatever local grievances they also drew attention to – was for faster demobilisation. And nowhere was there any suggestion of violence against the officers. These were not riots. However spontaneous, they were disciplined demonstrations by men determined to emphasise to the British government their justified desire for an early return home.

Mauripur, not many miles from Drigh Road, was the first station to respond to the news of our action. Meeting on the day of our visit from the Air Commodore, the Mauripur men put the slow rate of demobilisation at the head of their list of grievances and decided on a stay-in strike, though they kept the essential medical and canteen services running.

The men were addressed the following day by the Inspector-General of the RAF, Air Marshal Sir Arthur Barratt, who was on a welfare inspection tour. He answered many questions about demobilisation and repatriation, but the men were not satisfied and demanded that parliamentary representatives should visit them, so that they could impress upon the MPs the strength of their feelings about demobilisation. The Inspector-General then appealed to the men to return to work forthwith, but they refused and continued the strike for four days.3

The action in Ceylon began on 23rd January with the men of No. 32 Staging Post at Negombo, who refused to service aircraft after hearing of the “sit down” strike at Mauripur. The men complained about poor administration and lack of facilities for sport and entertainment, but their main grievance was the slow rate of demobilisation. The action spread to the rest of the Negombo station, including the Communications and Meteorological flights, and then to other Ceylon stations – Koggala, Ratmalana and Colombo. The BBC is said to have been the villain here. “It was apparent,” said a SEAC (South East Asia Command) report later, “that broadcasts made by the B.B.C. on January 24th and 25th were largely responsible for bringing out units where feelings were still in the balance. These broadcasts, for some reason, largely destroyed the good work which had been done by Commanding Officers and Unit Commanders in dealing with their men”.4

Cawnpore, with some five thousand personnel, was the largest RAF station in India. There were the usual complaints about food and living conditions, in addition to the major issue of demobilisation, and a special grievance at this station was what the men thought was the abuse of Class B release. In whatever country they were serving, most men were released under a scheme (Class A) which allocated airmen to groups according to their age and length of service. Each man knew to which group he belonged (Group 20, say, or Group 35) and knew that the groups would be released in turn. Certain men, however, could obtain earlier release (Class B) if they had particular skills needed in post-war reconstruction, especially in the building industry. One can imagine the resentment when it was being said at Cawnpore that in the previous few weeks a ballet dancer, a bell-ringer and a theological student, as well as a bricklayer’s labourer and a plumber’s mate, were all “getting out” under this “help in reconstruction” scheme.5

Before the Cawnpore men had decided on strike action, the station was visited by Air Marshal Sir Roderick Carr, head of the RAF in India. LAC Mick Noble, who became the official spokesman for the strike committee, wrote later, “We placed our grievances before him but received no satisfaction. He made it clear that he had …(come) …from Delhi to prevent us from taking strike action. A strike committee had been formed late Friday night …and the men were later informed about the unanimous decision to strike and fully endorsed the action. The strike … lasted over a period of four days.

“The strike committee conducted the administration of the unit and men paid no heed to the officers’ appeals for them to return to work. All the orders which came from the committee were fully endorsed and carried out by the men. Men working in the essential services were instructed to continue. Prohibition (i.e., no alcoholic drinks) was introduced for the period of the strike.”

“A daily bulletin,” continued LAC Noble, “was published, which outlined the discussions and the decisions taken at the strike committee meetings. The men were kept continually informed by numerous meetings. Each decision of the strike committee was taken to the men for support during the entire period of the strike.”6

LAC Harry Darby, one of those involved at Cawnpore, later wrote, “I think we were out for four or five days altogether, with the officers wandering round the billets talking to us all in little groups and asking questions, etc.” And he added, virtuously, “Four of us in my billet played bridge day and night for the whole of the time we were out, and not a penny was gambled on any game.”7

At Seletar, Singapore, more than four thousand men were involved in the strike. It began with a meeting in the canteen, which was filled to capacity, on the evening of 26 January. After the lights had been put out, a chairman – who was addressed throughout the meeting as “Mr Speaker” – stood on a table and checked that all Seletar units were represented. There was also at least one representative from Kallang, the smaller Singapore base.8

Next morning the men were addressed by the CO, Group Captain Francis, but they were dissatisfied with his response and demanded a meeting with Air Chief Marshal Sir Keith Park, the Air Officer Commanding, South East Asia Command, who was based nearby. He arrived in the afternoon, spoke to the men and, after answering questions on release and repatriation, promised to report to London the strength of their feelings. “Moreover,” said the official report, “he gave facts and figures to prove that the R.A.F. had not been treated unfairly by comparison with the Army or even the Navy”.9 But the men did not believe his “facts and figures” and began to walk out in disgust before he had concluded the meeting.

During the strike the Seletar men passed a number of resolutions, agreeing among other things that there must be no violence and no picketing, and that Air Sea Rescue would carry out normal duties.10 A statement of grievances was adopted, including complaints about the wretched food and the lack of facilities for recreation, but making it clear that demobilisation was the key issue. The emphasis here was a little different, with the statement saying, “We have nothing against the Labour government. This is not a political strike. Our quarrel is with the higher-ups responsible for the delays and discrimination in repatriation and demobilisation”.

Essential services were maintained throughout the strike, but Kisch notes that “aircraft arriving at the landing strip were unable to take off again as refuelling facilities were not available. In the camp discipline was preserved, officers were treated respectfully, saluting was punctilious”.11 Delegates were sent from Seletar to Kallang, the smaller Singapore base, to call on the men there to join the strike. Sir Keith Park also rushed to the base, hoping to head off any action there.

The men of Kallang met at 6.30 p.m. on the Sunday (27 January) to consider their response to what Sir Keith had said to their representatives that afternoon. There seems to have been a large majority in favour of a strike and a decision to take immediate action would probably have been taken but for the intervention of Aircraftman Norris Cymbalist. Cymbalist told the men that before they could go on strike there were some things they had to be certain of. They had to be sure that they could keep essential services running, in order to avoid hardship and loss of life; they had to command the support of the whole unit; they had to be clear what they wanted from the strike; and they had to be sure there was no other way of obtaining redress for their grievances.

The men listened to the AC in respectful silence, agreed at once to adopt his suggestion of a committee and promptly elected Cymbalist himself to be its chairman. This committee set about organising a further meeting of the men at 10.30 that night to decide whether to have a 48-hour strike. There was nothing secret about this. Cymbalist and others called at the sergeants’ mess to invite them to attend, and they went out of their way to inform several of the officers that the meeting was taking place.

The tension that had been developing during the evening was heightened further when it was learned that six men, including some members of the committee, had been arrested for incitement. It did not help that several officers, including some who were not stationed at Kallang, were present at the meeting. It was a noisy gathering. The earlier calls for a strike were repeated. Men demanded the release of their arrested colleagues. There was a great deal of shouting, often several people calling out at once. Some of the officers had a great deal to say and, amid all the hubbub, one of them was involved in an altercation with Cymbalist and ordered the arrest of the AC.

There was strong feeling about the arrest of Cymbalist and the other six; the atmosphere remained tense; and after midnight the CO, Group Captain C Ryley, agreed to meet some of the men. There is no record of who said what at this meeting, but, in effect, a deal was struck, though I am sure that the CO would reject the word “deal”. However it came about, the men agreed not to strike and the CO agreed to release the seven prisoners, though this was “without prejudice to re-arrest and disciplinary action”.

At 08.45 next morning, the Group Captain reported, 100 per cent of the men “returned to duty”, which suggests that some of them might have taken their own strike action the day before. But there was no mass abstention from duties, and the CO wrote to Park, “I think the men have behaved extremely well in face of highly skilled Communist propaganda. You might care, if you have a moment, to send them a ‘bouquet’ which I can publish in S.R.O.s [Station Routine Orders]. I feel they have deserved this.”12

At Dum Dum, the aerodrome near Calcutta, twelve hundred men went on strike. The Times reported, “They have no complaints against the authorities at the camp, with whom they are on the best of terms. The commanding officer had a friendly discussion with them when notice of strike was given. Yesterday a delegation of the strikers had a talk with Air Commodore Battle, Group Captain Slee, who commands the station, and with Major Wyatt, of the Parliamentary delegation visiting India, who had communicated with the Air Ministry.”13

Mr C Miller, of Wigan, wrote recently, “I was one of the strikers at the Dum Dum airstrip at Calcutta and one of the main ‘beefs’ which we had … was the fact that the large liners such as the ‘Queen Mary’ were being used to ship GI brides back to the United States. Yet the Air Ministry persisted in telling us that they couldn’t bring us back because of shortage of shipping!!! They even had the nerve to add that the water outside Bombay Harbour was not deep enough for large liners, and men would have to be conveyed out to them by tender! Needless to say, we said we did not mind one bit being thus tendered out!”

Mr Miller kept a diary during the strike, and he noted:

January 25th: Strike meeting in hangar. “Groupy” (Group Captain Slee) present, tries to answer demob, etc., but frankly admits sympathy with our cause. “Would strike himself if he was an airman”. We hear quite a good statement (a “taffy”). Resolution to strike carried amidst enthusiastic roars. Starts from midnight tonight. Exceptions to striking are cooks, markers and station wagon drivers!

January 26th: On strike! Meeting called for 12 p.m. Grievances put to Woodrow Wyatt, member of delegation touring India …He attempts to answer them, but has to admit to several of our points. “Groupy” and an Air Commodore also present. He reads out two signals from higher up, which more or less are on the consequences of striking. This doesn’t improve matters. Now comes a split within our own ranks. I line up with the minority in favour of giving government seven days deadline during which we resume work, failing which we resume strike. Majority favour continuing strike until a reasonable reply is received from Air Ministry.

January 27th: Another meeting. Written vote taken on issue, “deadline” or “strike”… Meanwhile, signals from Ministry show that “Groupy” is in it up to the neck and will have to take disciplinary action if strike is not broken!

10 a.m. Further meeting. “Taffy” will no longer lead the “strikers” on such a small majority. Groupy opens the meeting by an appeal for a return to work, having received more signals stating that action will have to be taken, etc. He then leaves… Eventually, majority favour a “deadline” of 14 days. Groupy is recalled and thanks us in a heartfelt manner. Work resumes from 6 p.m.

“There were subsequent reactions,” Mr Miller wrote, “but fortunately we had an understanding that there would be no victimisation. This understanding proved to be invaluable in some cases.”14

The men at Allahabad answered a call to meet in the camp canteen at night. The lights were put out and someone stood on a table and, speaking with a pencil in his mouth to disguise his voice, proposed that they should begin a strike the next day. Next morning, marshalled by their corporals, the men marched to the parade ground and then to the camp cinema. There they elected Bernard Shilling to present their case to the senior officers.15

Ex-LAC Des Streatfield, of South-West London, remembers events at the Racecourse Camp at Delhi. There was a meeting in the cinema “when we were addressed by Air Marshal Sir Rodney Carr … Our camp station warrant officer came on to the stage, made it known that mutiny was a shooting offence but for the time being we would still be fed and housed. He then came out with this request: would we all please stand up when the air marshal took the stage!”16

Burma was also involved. Men of the No. 194 (Transport) Squadron, stationed in Rangoon, came out on the 29th. They complained about living conditions and the quality of the food as well as the rate of demobilisation, but what triggered the strike was an order for a daily working parade. Having made their protest, they returned to work the next day, but Air Marshal Sir Hugh Saunders, in charge at Air Headquarters, Burma, felt that the situation was still tense and was anxious to avoid further provocation.17

The Times also reported briefly on strikes at Almaza and Lydda in the Middle East, and at Poona and Vizagapatam in India. In general, however, considering the scale and importance of the strikes, they were not well reported in the British press. Much of what did appear was based on official handouts, with nothing from the strikers themselves and no serious assessment of the grievances. There was more comment than fact, and there were also, of course, some more fanciful stories. The Daily Mail’s Special Correspondent in Cairo, for example, reported that the source of the RAF strikes was a “well-laid plot”. RAF security and intelligence officers, he claimed, thought that the strikes “were organised over a period of weeks either by airmen-agitators, who contacted each other in code, using the RAF wireless system, or by airmen travelling between stations”.18

That raises some interesting questions. Who could have installed airmen-agitators in the signals sections of more than 60 units? Or which high-ranking officer could have sent, within a few days, airmen travelling from Egypt to India, from Ceylon to Singapore, with orders to the local agitators at all those units, “Have a mutiny on your station tomorrow”. The mind boggles.

II

These strikes were largely successful in meeting their objectives. On most of the affected camps the food improved, as did various aspects of the living conditions. Most importantly, there was also a speeding up in the rate of demobilisation, and within the next few months an extra 100,000 RAF men were released. Early in February a statement on RAF demobilisation covered five months instead of the usual three. Between February and June, groups 27 to 35 would be released.19 And on 1 March came the announcement of a further speed-up. Group 35 would now be demobilised by the end of May

John Strachey, the Under Secretary of State for Air, was worried that the speeding up would be seen as giving way to the strikers. On 1 March he was writing that the first announcement had been “looked on by some people as a concession to the men” and “I fear that this announcement of a further speed-up will be looked on in the same way”. But there was worry, both in Britain and overseas, about the possibility of further outbreaks, so there had to be positive news for the men.

The strikes had other far-reaching effects. Accusations appeared in the British press that the strikers were weakening Foreign Secretary Bevin’s hand at the United Nations; and there were important consequences for India. First, men of the Indian Air Force, who had grievances of their own, followed the example of their British colleagues. There were strikes at a large number of stations, including Cawnpore, Bombay, Allahabad and Jodhpur. At Drigh Road the Indian airmen had a short hunger strike. Again, the men were orderly and there was no violence.

The Royal Indian Navy followed. Three thousand ratings mutinied in Bombay, the principal naval base, and many of them carried the flags of the Indian National Congress and the Muslim League when they demonstrated in the city.

When some of the ratings ashore were involved in skirmishes with soldiers, the mutineers on board the ships in the harbour trained their guns on the city and threatened a bombardment. Lieut-General R M M Lockhart, GOC, Southern Command, assumed command of all navy, army and RAF forces, with instructions to restore order as quickly as possible. The RAF was ordered to prepare to sink the ships in the hands of the mutineers. The men surrendered, however, mainly in response to appeals from leaders of the Indian National Congress. There followed four days of riots in the city, and there were hundreds of casualties. Further naval mutinies occurred at Calcutta, Madras and Karachi. There was considerable loss of life at Karachi, where the army commander ordered the use of artillery against the mutineers.20